The Skills Beneath the Skills: Executive Function and Self-Regulation

We usually think of school readiness as knowing numbers, letters, or shapes. But those achievements sit on top of something deeper: the skills to focus attention, adjust to changes, and manage emotions. These underlying abilities, called executive function, are what make it possible for children to learn, grow, and connect with others.

The Core of Executive Function

Executive function is a group of mental skills that support goal-directed behavior. These skills continue developing, but are especially critical in early childhood.

- Working Memory: Holding and using information

- Cognitive Flexibility: Adjusting to changes

- Inhibitory Control: Resisting impulses

Together, these skills help children stay focused, navigate changes, and keep trying even when a task feels tough (Bull et al., 2011).

Executive Function and Self-Regulation

Self-regulation is how children use executive function in daily life. It’s what helps a child stay calm during a tricky puzzle, share materials even when they’d rather not, or adjust when the schedule shifts.

Decades of research show that self-regulation is one of the strongest predictors of school readiness and long-term success – sometimes even more than IQ. Children with developed executive function are more likely to thrive in academics and relationships, even when life throws challenges their way.

- Mathematics: Working memory is linked to learning and applying early math skills, from counting to problem-solving (Bull et al., 2011).

- Literacy: Inhibitory control helps with reading by keeping focus on text, ignoring distractions, and sticking with decoding (Blair and Razza, 2007).

- Classroom Engagement: Regulating emotions and impulses supports persistence, motivation, and strong teacher relationships (Eisenberg et al., 2003; Valiente et al., 2003).

What Self-Regulation Looks Like in the Classroom

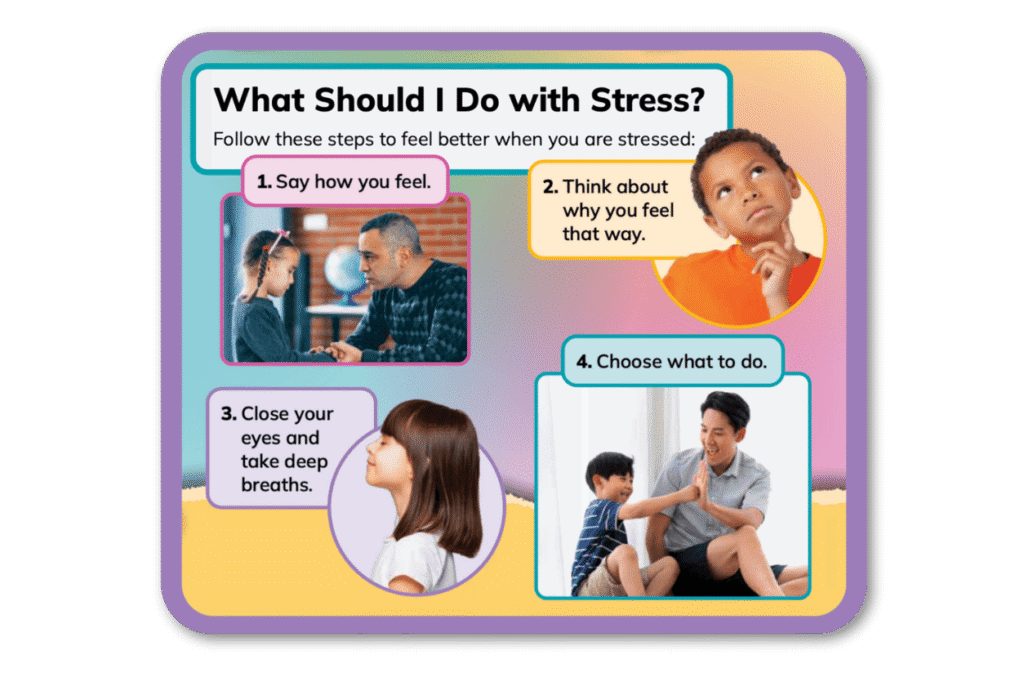

Self-regulation isn’t an abstract idea. It shows up in everyday skills students can learn through modeling and practice.

1. Working Memory

- Remembering coping strategies under stress

- Setting goals and tracking progress

- Knowing when to ask for help

2. Cognitive Flexibility

- Identifying feelings and practicing optimism

- Building resilience after facing challenges

- Adjusting strategies when things change

3. Inhibitory Control

- Using calming strategies like breathing

- Pausing to think before acting

- Choosing kindness, fairness, and respect

Building Self-Regulation Skills in the Classroom

While self-regulation may seem like a characteristic, it is actually a collection of skills and strategies that can be learned.

If students learn explicit strategies and practice using them, they will grow in their ability to self regulate. And approaching those skills with a growth mindset helps students have patience with their own learning process.

Buffering Stress to Build Readiness

Not all children arrive in your classroom with experience in practicing self-regulation. Stress and poverty can affect the brain areas needed for learning and memory (Hanson et al., 2011). Research shows that supportive environments where children practice self-regulation can reduce the impact of stress and help students stay engaged in learning (Diamond and Lee, 2011; Blair and Raver, 2015).

By empowering students to develop skills that foster calm, confidence, and kindness, teachers can help all learners develop a foundation for success.

When classrooms make space for executive function and self-regulation, children are better prepared not just for academics, but also for the social and emotional demands of school and life. By modeling strategies, weaving them into routines, and giving children repeated opportunities to practice, teachers open doors for every learner and provide tools that last far beyond the classroom.

Ava, a student, has used Studies Weekly in her kindergarten classroom. She learned skills like setting and keeping goals, adjusting to changes, and choosing to act respectfully. Her teacher asks the students to put away their toys, line up, and walk to the rug. Ava wants to keep playing, but she remembers she set a goal to follow her teacher’s instructions the first time she hears them. She uses what she has learned to adjust to the change in activities with a positive attitude. She chooses to be respectful by lining up instead of running to her favorite spot on the rug. In minutes, she has used several important executive function skills she learned about and practiced with Studies Weekly!

Social Studies

Standards-aligned lessons that spark curiosity

Studies Weekly Online

Less prep, more impact on students

Health & Wellness

Boost your students’ emotional wellness skills

Science

Encourage students to investigate through hands-on learning

Sources

Blair, Clancy, and Rachel Peters Razza. “Relating Effortful Control, Executive Function, and False Belief Understanding to Emerging Math and Literacy Ability in Kindergarten.” Child Development 78, no. 2 (March 1, 2007): 647–63.

Bull, Rebecca, Kimberly Andrews Espy, Sandra A. Wiebe, Tiffany D. Sheffield, and Jennifer Mize Nelson. “Using Confirmatory Factor Analysis to Understand Executive Control in Preschool Children: Sources of Variation in Emergent Mathematic Achievement.” Developmental Science 14, no. 4 (November 23, 2010): 679–92.

Diamond, Adele, and Kathleen Lee. “Interventions Shown to Aid Executive Function Development in Children 4 to 12 Years Old.” Science 333, no. 6045 (August 19, 2011): 959–64.

Eisenberg, Nancy, Carlos Valiente, Richard A. Fabes, Cynthia L. Smith, Mark Reiser, Stephanie A. Shepard, Sandra H. Losoya, Ivanna K. Guthrie, Bridget C. Murphy, and Amanda J. Cumberland. “The Relations of Effortful Control and Ego Control to Children’s Resiliency and Social Functioning.” Developmental Psychology 39, no. 4 (July 2003): 761–76.

Hanson, Jamie L., Amitabh Chandra, Barbara L. Wolfe, and Seth D. Pollak. “Association between Income and the Hippocampus.” PLoS ONE 6, no. 5 (May 4, 2011).

Valiente, Carlos, Nancy Eisenberg, Cynthia L. Smith, Mark Reiser, Richard A. Fabes, Sandra Losoya, Ivanna K. Guthrie, and Bridget C. Murphy. “The Relations of Effortful Control and Reactive Control to Children’s Externalizing Problems: A Longitudinal Assessment.” Journal of Personality 71, no. 6 (December 2003): 1171–96.