Teaching Irish American History

You only need to walk into a store and see St Patrick’s Day decorations to know Irish Americans have profoundly impacted our country’s culture. But what brought so many Irish immigrants to the United States?

This overview of Irish American history can help you teach students why they see so many Irish influences today.

First Wave of Irish Immigration to America

When you hear Irish immigration, you probably think of the people who fled to America during the Great Potato Famine of 1845. However, the first big wave of Irish immigrants came in the early 1700s, according to Catherine B. Shannon from Westfield State College.

Most of these immigrants traveled from Ulster – a province in northern Ireland – to escape religious persecution and economic hardship. Members of the Anglican Church of Ireland passed the English Penal Laws to prevent Roman Catholics and Protestant dissenters (non-Anglicans) from attending school, owning land, voting or running for public office. Landowners also kept raising rent while farmers suffered bad harvests, making food scarce for working-class citizens.

Seeking a better life, over 200,000 Ulster Protestants – as they were called – traveled to the US between 1700 and 1775, wrote Shannon. Many came as indentured servants, exchanging four to five years of labor for passage to the New World. For these poor Irish immigrants, it was a price worth paying. In their new home, they could buy land, practice their faith, and have equal standing in their communities.

Many Ulster Protestants settled in Delaware, Maryland, and Pennsylvania where there was better land, greater religious tolerance, and more job opportunities.

Second Wave of Irish Immigration

In 1845, the Potato Famine spread across Europe, but nowhere did it cause more devastation than in Ireland. Potatoes were the only crop that working-class Irishmen could grow on the poor land the wealthy British landowners allotted them. According to Irish Famine Facts by John Keating, the average adult in Ireland ate between 11 to 14 pounds of potatoes per day.

When the potato crops began to fail, working-class citizens had nothing to live on. About one million of them died of starvation or diseases caused by lack of food.

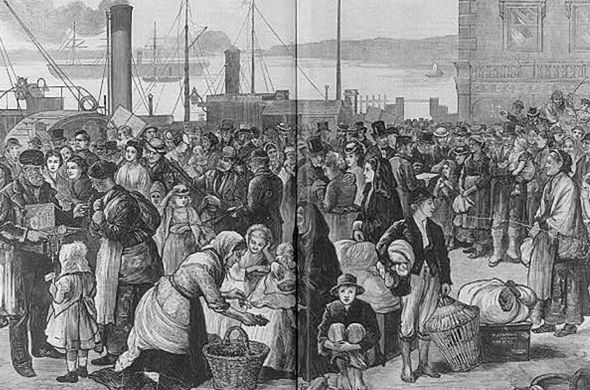

Once again, the Irish looked to America for hope.

Between 1841 and 1850, they came by the thousands, making up about 50% of US immigrants, according to Britannica. Many of them spent whatever money they had left on their passage, so they settled in the port cities they landed in. It wasn’t long before New York City had more Irish residents than Dublin, according to MacCaulay Honors College.

The growing population and lack of affordable housing forced Irish immigrants to move into tenant houses built for single families. They lived in cellars, attics, and alleyways without enough running water and sewage systems to go around. This unhealthy living situation bred diseases like cholera, typhus, and tuberculosis. But instead of helping these Irish immigrants, many US citizens blamed them for creating these unsanitary conditions, according to the Library of Congress.

Religious Persecution

This second wave of Irish immigrants – most of them Catholic – may have escaped the potato famine, but they continued to face religious persecution. Many US citizens came from a Protestant background and held negative views of the Roman Catholic Church. Some even feared the Pope and his Vatican army would invade the country and, with the help of the Irish, enforce Catholic canon as the law of the land, according to Conspiracy Theories in American History: An Encyclopedia.

These biases led to verbal attacks and sometimes mob violence. In 1831, anti-Irish mobs burned down St. Mary’s Catholic Church in New York City. During the Bible Riots of 1844 in Philadelphia, mobs set fire to churches and immigrant homes, killing 13 people.

Entering the Workforce

Desperate to make ends meet, Irish immigrants accepted whatever jobs they could get, whether it was cleaning yards and stables, pushing carts, or unloading ships. Businesses took advantage of their plight and hired immigrants to do dangerous jobs, including working in coal mines factories and building railways and canals.

According to the Library of Congress, “Railroad construction was so dangerous that it was said, ‘[there was] an Irishman buried under every tie.’”

Irish immigrants earned an average wage of 75 cents a day and had to work 10-12 hour shifts, seven days a week, according to MacCaulay Honors College.

Because Irish immigrants were willing to work for so little, many employers fired union workers and replaced them with cheap labor, causing locals to resent Irish immigrants. Organizations like the American Protective Association (APA) and the Ku Klux Klan took their anger out on Irish Americans, according to the Library of Congress.

Other businesses discriminated against Irish immigrants by blatantly refusing to hire them. According to History.com, they’d state in their job newspaper advertisements, No Irish Need Apply.

Irish men weren’t the only ones needing to find employment. Irish women worked in cramped, dirty factories for long hours with very little pay. Others earned money as chambermaids, cooks, and caretakers for wealthy families, according to MacCaulay Honors College.

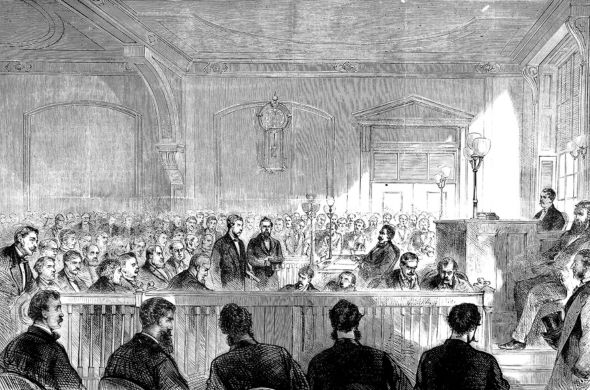

Political Discrimination

US citizens with anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiments formed the nativist American Party. This party claimed to uphold American ideals by only voting for Protestant US-born citizens.

In 1854, the American Party gained power in Massachusetts and mandated the reading of the King James Bible in public schools, disbanded Irish militia units, confiscated their weapons and deported nearly 300 poor Irish immigrants.

In Louisville, Kentucky, in August 1855, American Party members guarding the polling stations on an election day attacked Irish Catholics and set immigrant homes ablaze, killing between 20-100 people. Of course they were never prosecuted for these assaults, and Irish Catholics had to flee the city to escape persecution.

Racial Tension

Because white, native-born citizens at this time saw labor jobs as degrading, Black and Irish Americans competed for these positions, which brewed racial tension between these ethnic groups, according to MacCaulay Honors College.

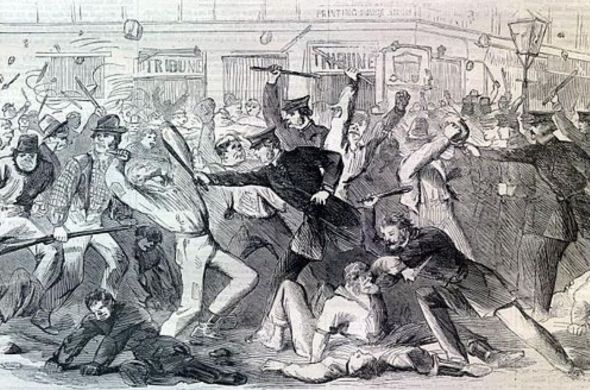

When the Civil War broke out, white men – including Irish Americans – were drafted into the Union Army. Black Americans, however, were not required to enlist, causing even more friction between these two groups.

Draft riots broke out in several major cities. In 1863 in New York, Irish immigrants and other working-class white men burned down a draft office and attacked police officers. They then turned on innocent African American bystanders. When the riot was over, they had murdered 18 Black Americans, injured countless others, and destroyed $5,000,000 worth in property – including a black orphanage according to MacCaulay Honors College.

Gaining Political Power

Despite religious and political persecution, the tables began to turn for Irish Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They became a powerful force by creating political machines – systems where “bosses” gave immigrants food, shelter, and immigration services in exchange for votes.

Irish Americans embraced the chance to thrive in their new country and voted in higher numbers than any other ethnic group. Their political machines became so effective that they got William R. Grace elected the first Irish-Catholic mayor of New York City in 1880 and Hugh O’Brien the first Irish-Catholic mayor of Boston in 1884.

One of the most famous political machines – run by boss William Tweed of Tammany Hall – was under Irish American control for more than 50 years, according to the Library of Congress.

While these political systems led to abuse of power, they also allowed Irish Americans to help each other get better jobs and provide for their families. Thanks to the social services provided by political machines, Irish Americans could thrive in their new home.

While Irish immigrants were not perfect, their legacy of hard work and sacrifice can inspire your students to rise above their circumstances and create a better future.