On Education: Creating a better Multicultural Curriculum

How do you teach today’s culturally and socio-economically diverse students when often their history and literature curricula are predominantly Eurocentric?

Because we know our students represent a wide swath of skin tones, ancestry, experiences and languages, we try to include multiple perspectives in our publications.

As Samantha Washington explained in her September 2018 article in The Century Foundation, studies show that students in diverse public schools harbor less racial prejudice and more self-confidence. She advocated that “equitable education reform must be invested in diversifying not only classrooms, but lesson plans, too.”

“That students with vastly different backgrounds are still being taught that only one history is worth knowing reveals what has always been a deeper question in American education: whose history is essential, and what are we teaching students when we tell them that theirs is not? In the fight for racial equity in the classroom, we must stress the importance of students learning from a curriculum which reinforces that their own histories, and, by extension, their own identities, matter,” she concluded.

But how can educators value the histories of all their students?

“As our country and schools become more ethically and culturally diverse, elementary teachers must have tools to help them plan for broadening the perspectives of the children they teach,” said professors Joyce H. Burstein and Lisa Hutton in Social Studies and the Young Learner in 2005.

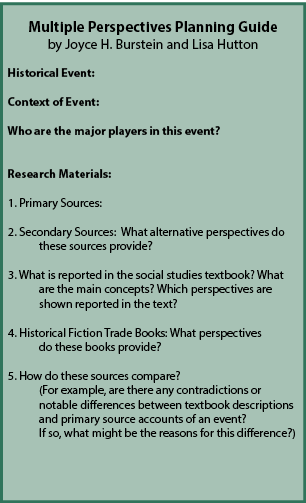

Recognizing that some textbooks don’t provide multiple perspectives, they shared a fabulous teaching strategy for elementary educators: a Multiple Perspectives Planning Guide for tackling historical events that have multiple viewpoints. Of course, most of history has at least two sides to it — if not more — so this guide works well for any social studies classroom.

The guide focuses on a historical event, and takes students through its context and the major players there. Students delve into both primary and secondary sources from the event, looking for different viewpoints and perspectives. Burstein and Hutton also suggest using historical fiction trade books as sources, especially at the elementary level, because many are written by authors who hail from unique perspectives not always included in textbooks.

This learning strategy validates different cultural experiences, allows children the chance to identify with histories that truly reflect their own and others’ heritage, while also teaching them important critical thinking and analysis skills, and an ability to recognize complex situations.

In explaining the guide, Burstein and Hutton gave the example of children playing and resolving disputes in school yard. When problems happen at recess, “Children naturally want to tell their side of a story …. Students are burning to report their version of what happened.”

“Teachers need to capitalize on this natural inclination to have ‘their story told’ when teaching history,” they continued. “Historians are like a person who suddenly comes upon the scene of the playground dispute. The historian hunts for different accounts, artifacts, evidence and viewpoints of time periods in history.”

Looking at the bigger picture, today’s textbooks and lesson materials need to include these varied accounts and viewpoints. They cannot include token remarks highlighting important contributions from women, minorities and other cultures. Instead, these perspectives must be fully integrated into the curriculum, as Paul C. Gorski explains at EdChange.org.

Gorski encourages true curriculum reform. In his listing of “Key Characteristics of a Multicultural Curriculum,” Gorski explains that creating a truly multicultural curriculum includes changes to the following within the classroom:

- Teacher delivery must address different learning styles and perspectives and challenge typical power dynamics in the classroom.

- Content must accurately represent the contributions and perspectives of all groups, while avoiding stereotypes and language that represents a bias or one perspective.

- Educators should incorporate diversity in learning materials — both in language and perspective — and also type, i.e: texts, newspapers, videos, images, games, etc.

- Present content, events and movements from a variety of lenses, and through more than just a few “heroic characters.”

- Include the perspectives and experiences of your students and their heritage, and encourage ways to connect these with relevant historical events.

- Hold honest discussions about racism, sexism and other forms of oppression, and connect students to their local and global community.

- Constantly evaluate and assess curriculum “for completeness, accuracy, and bias.”

As Burstein and Hutton explain, “Providing options in perspective helps children understand that history and the social sciences are made up of many different sources and points of view.”

Today’s students hail from a diversity of experiences, and social studies are a great way for them to explore those perspectives and their place in the world.

To see how Studies Weekly incorporates multiple perspectives in our publications, request a free sample.