Women's History Month: Women of Color, Women of Change

Every year, Women’s History Month is a great opportunity to delve even deeper into history and hear from new voices and experiences.

As you teach about women’s many contributions to history, here are a few historic women of color whose actions brought about significant change.

Women of Strength

Lozen

Lozen was an Apache warrior active during the 1870s and ’80s until her death in 1889. According to Biography.com, her brother said of her: “Strong as a man, braver than most and cunning in strategy, Lozen is a shield to her people.”

According to historians, Lozen is notable because she was respected as a warrior within her tribe in an era when women rarely rode into battle beside men. In one 1886 battle, she and another female warrior, Dahteste, negotiated with U.S. authorities on Geronimo’s request.

She also helped during multiple battles because she had the ability to know when enemies were near — her hands would tingle or turn purple, according to some accounts, when she faced the enemy.

Constance Baker Motley

Constance Baker Motley was a woman of firsts. A daughter of immigrants from the West Indies, she was the first black woman accepted to Columbia Law School, the first black woman to argue a case in the U.S. Supreme Court, the first black woman elected to the New York State Senate and appointed Manhattan Borough president, and the first black female Federal Court judge, according to biography.jrank.org and blackpast.org.

She took on many landmark cases during her legal career, and won most of them. She was part of the legal team for Brown v. Board of Education and other school segregation cases that followed; she was lead council in James Meredith’s case against the University of Mississippi; and she defended Freedom Riders during the Civil Rights Movement.

As a politician and a judge, she worked to improve conditions and educational opportunities for the underprivileged. Before her death in 2005, she earned many national awards and honorary degrees, including the Presidential Citizens Medal in 2001, according to Hobart and William Smith College.

Yuri Kochiyama

In a 1965 Life magazine spread, one image shows Yuri Kochiyama cradling the head of a dying Malcolm X. But Kochiyama is not just a random person in a photo. A Japanese American, Kochiyama was a lifelong activist who worked for freedom and equality for all.

In her early 20s, she and her family joined other Japanese and Japanese Americans who were forced into an internment camp in 1942 during World War II. This sparked her political activism, and after moving to Harlem in New York and connecting with Malcolm X, she became involved in the Civil Rights Movement.

After her work there, she extended her work to social justice, according to a 2014 NPR broadcast. Throughout the decades, she agitated for Puerto Rican independence, lobbied for the release of political prisoners, worked for better job opportunities for minorities, including Chinese construction workers, and advocated for wartime reparations for Japanese Americans.

“She became a foremost bridge between the Black and Asian movements and between East and West Coast activists,” according to the Densho Encyclopedia. Kochiyama died in 2014.

Dolores Huerta

Dolores Huerta, born in 1930, was the co-founder of United Farm Workers. She worked alongside César Chavez to improve working conditions and ensure the rights of migrant workers in the United States.

She also had an important part in the passing of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975 — the first law in the U.S to grant farm workers in California the right to organize and negotiate for better wages and working conditions.

She earned multiple awards, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012. According to doloreshuerta.org, at that ceremony, she said, “The great social justice changes in our country have happened when people came together, organized, and took direct action. It is this right that sustains and nurtures our democracy today.”

She continues to speak out on social issues, including: immigration, income inequality, and rights for women, Latinos, disabled and elderly.

Women of Compassion

Wilma Mankiller

Wilma Mankiller of the Cherokee Nation worked throughout her life to improve housing, infrastructure, education, and employment conditions for members of her tribe. Because of her efforts, Mankiller became deputy principal chief of the Cherokee Nation in 1983. Then in 1985, she became the first female principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. She served as principal chief until 1995.

During her time as chief, she oversaw a community project to build a water system for tribal residents living without running water. She also expanded educational, healthcare, and job-training facilities and opportunities across the Cherokee Nation, some 170,000 people strong at the time.

Her efforts garnered recognition and awards, including Woman of the Year by Ms Magazine in 1987 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, in 1998.

Elouise Cobell

In 2009, Elouise Cobell of the Blackfoot Confederacy won an important class action suit, Cobell v. Salazar, for American Indians. The lawsuit accused the federal government of more than 100 years of mismanagement of the Indian Trust Funds for lands held in trust by the United States. After 15 years of languishing in the courts, the government approved a $3.4 billion settlement, known as the Claims Settlement Act of 2010.

Cobell never saw the fruit of her labors because she died of cancer just months after the court’s final approval of the settlement. But according to filmmaker Melinda Janko, Cobell’s efforts put money into the pockets of hundreds of thousands of American Indians — back where it belonged.

Ileana Ros-Lehtinen

Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, born in Havana, Cuba, in 1952, became the first Hispanic woman elected to Congress in 1989. According to the National Women’s History Museum, during her work as a teacher and principal, “Ros-Lehtinen was inspired to seek public office by the parents of her students. She wanted to ‘fight on their behalf for a stronger educational system, lower taxes, and a brighter economic future.’”

While in Congress, she advocated for the Women Airforce Service Pilots, or WASPs, to receive the recognition they deserved as veterans of WWII. She also promoted LGBTQ+ rights and sponsored the Violence Against Women Act.

Ros-Lehtinen’s election also opened doors and broke barriers for other Hispanic women in Congress and other elected positions today.

Women of Dignity

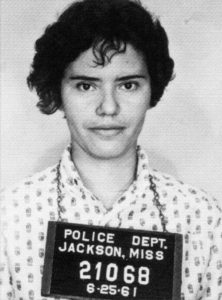

Courtesy Jackson Mississippi Police Department, Wikimedia Commons

Mary Hamilton

What is in a name?

Mary Hamilton demonstrated the importance of her name, as well as the full names of her fellow African Americans by standing up for respect in a unique way.

Hamilton appeared in an Alabama court in 1963 in connection with local Civil Rights activities. The prosecutor in the case called Hamilton by her first name, as was the custom at the time when addressing African Americans in a courtroom. White people were usually addressed with Miss, Mrs., or Mr. From the court papers, at casetext.com:

“Q: What is your name, please?

A: Miss Mary Hamilton.

Q: Mary, I believe — you were arrested — who were you arrested by?

A: My name is Miss Hamilton. Please address me correctly.

Q: Who were you arrested by, Mary?

A: I will not answer a question — your question until I am addressed correctly.”

The court fined Hamilton and jailed her for her refusal to answer questions on the witness stand. Hamilton appealed, and her case went all the way to the Supreme Court. The Court ruled in her favor in 1964.

Hamilton’s refusal to be disparaged in this small but significant way was a “groundbreaking victory for African Americans within the routine nomenclature and decorum of legal proceedings at that time,” according to the Thurgood Marshall Institute.

Lena and Katherine Carper

Many understand the impact of the court case Brown v. Board of Education on segregated schools and the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s. But that lawsuit started because a few African American parents and children petitioned for equal treatment under the law.

Ten-year-old Katherine Louise Carper’s school day lasted more than eight hours because she could not attend the school in her local district. Instead, she walked across fields and unpaved roads and took a city bus to her segregated school 40 minutes away.

She and her mother, Lena Carper, were the first to sign on as plaintiffs in the lawsuit. Lena Carper and her daughter both testified in court.

At such a young age, Katherine didn’t fully realize the importance of her involvement and what it meant for the Civil Rights Movement. According to the Thurgood Marshall Institute, she “believes that her mother was just fighting for her to have a better education and quality of life.”

Sylvia Méndez

Before Brown v. Board of Education, there was Méndez v. Westminster.

Sylvia Méndez, born in 1936 and of Mexican and Puerto Rican heritage, experienced segregation on the opposite coast of Katherine Carper. In the early 1940s, Méndez was only nine years old when she was turned away from enrolling in an Orange County school in California designated for “whites only.”

This event led her parents and other families to sue the school district and win the landmark case, Méndez v. Westminster, in 1946. This case paved the way for Brown v. Board of Education seven years later and became instrumental in ending segregation in U.S. schools. Méndez continues to be a civil rights advocate today. In 2011, Méndez was a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom.